(Note: The following review features details of the plot of the first installment of Half-Life, including its climax.)

Over twenty years ago, the original Half-Life changed the world of first-person shooters. Advertisements for the game boasted that its predecessors, by comparison, could be summed up as “Run, shoot, run, shoot” ad nauseam. Following shooters would take cues from Half-Life for years to come, and the game itself started a franchise beloved by legions of gamers.

But given the technological restrictions of the era, as well as its much-maligned final levels, it was inevitable that modern Half-Life fans thought the first entry didn’t live up to its limitless potential, and would appreciate a full-blown remake of it. And that’s where Black Mesa came in.

Black Mesa, which was released earlier this year in its entirety for the first time, is a complete fanmade remake of Half-Life in the same engine as Half-Life 2. While the story remains more or less the same, at least in ways that are relevant in regards to its sequels, it significantly increases content, particularly in the final levels, and takes full advantage of two decades’ worth of advancement in game technology.

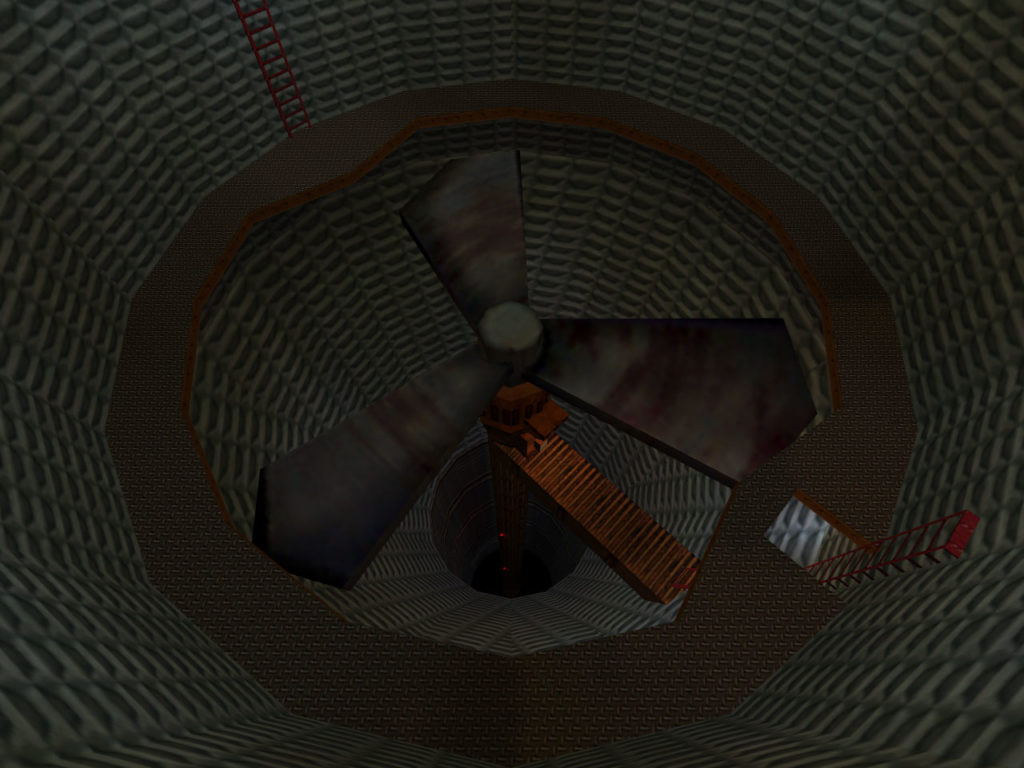

One of the first major advancements the player will notice is the atmosphere of the titular government research facility. The interiors of the Black Mesa Research Facility in the original Half-Life were often austere, metallic and sleek, like something out of the lower levels of the Academy in the X-Men movies. Black Mesa adds some much-needed realism by piling on the wear, rust and warning signs one would expect to see in the bowels of such a facility.

The last levels have been vastly expanded upon, with new enemies and mechanics abounding. One memorable foe is a zombified scientist wearing the same high-tech armored hazmat suit as the protagonist, with its onboard monitoring system audibly glitching and struggling to make sense of its occupant’s transformation.

Entirely new sequences are added, such as a high octane escape from scads of aliens impervious to the player’s weapons. Many more puzzles are added, which are never so difficult as to require a consultation of a walkthrough, nor so easy that no sense of accomplishment will be gained from solving them.

The scenery has been greatly altered overall, ranging from lush wetlands to bleak factories and shantytowns. While a commendable effort is made to create a world that is somehow recognizable while remaining distinctly alien, it’s questionable whether the resultant awe at its beauty is preferable to the trepidation of traversing dangerous landscape that was evoked by the level design of the original game.

The other levels stick more closely to the source material, though there is the occasional new set piece, such as a fast-paced shootout after falling into a trap set by enemy marines or a later attempt at stealth in a large aircraft hangar.

Also of note is the completely new original soundtrack, which of course features plenty of adrenaline-pumping fare for action sequences, but also some interesting surprises. The eerie, mournful main theme is oddly fitting for the game as a whole.

Aside from the updated engine, the biggest change is the overall push to make the game more cinematic on the whole. In addition to improved graphics, there is more effort put in to the development of characters. There is much more dialogue, and allies and enemies alike are rounded out.

Emergency alert broadcasts advise civilians to leave the area and take flashlights and radios with them, to head to a disease control center if they experience dizziness or hair loss, and to contact a military officer if they have firearms training. The player overhears a plea for help over the radio by a marine who is slowly bleeding to death.

All these elements make for an experience that is more immersive, and emotional for the most part. But there’s something to be said of the design of the original Half-Life that doesn’t quite translate to this new aesthetic.

In one notorious scene towards the beginning of Half-Life, the player pressed an elevator call button, and the car immediately came crashing down from above, carrying a few screaming scientists with it. The overall scene has been reproduced in Black Mesa. But now, the crash is no longer immediate. The occupants’ frantic pounding on the door and cries of how they don’t want to die are heard for several seconds until they plummet to their deaths.

It’s certainly more emotionally wrenching on most levels. But given that the fall doesn’t immediately follow the button press, it’s less obvious that it was indirectly due to the player’s actions — which was why the scene was so memorable in the original game.

The design of enemies is also flashier and more detailed, as could be expected given the modern gaming era’s newfound abundance of polygons. Half-Life‘s original monsters indeed look fairly primitive by comparison. But they had notable traits of their own that Black Mesa seems to have ignored.

Take the bullsquids, extremophilic bipeds that spewed globules of noxious bile at the player and could often be found near pools of toxic waste. Aside from a bizarre assortment of tentacles surrounding its mouth, it was pretty much featureless save for a pair of barely noticeable eyes. When killed, it let out a capitulatory whine disconcertingly similar to that of a family pet.

Its counterpart in Black Mesa, however, sports two glowing, angry, textbook-evil red eyes, with a repertoire consisting of snarls and exaggerated gargles. Its status as a threat and an enemy is emphasized, at the expense of its sense of mystery and otherworldliness.

Then there’s the final boss, the Nihilanth. The battle with the surprisingly weak and cowardly Nihilanth in Half-Life is often regarded as a major disappointment, but the character itself gave the player pause: It was suggestive of a human fetus, with empty black eyes and a tiny mouth that seemed to be in the middle of intoning something ominous. It occasionally gave cryptic messages to the protagonist, presumably through telepathy, that were perceived as an unsettling, reverberating moan.

In Black Mesa, the Nihilanth, as could be expected at that point in the game, presents a far greater challenge. But it now has fiery eyes that reveal an unquenchable rage, and its mouth is now lined with piranha-sharp teeth. The telepathic messages are still present, but they are now in the form of the guttural growl of a black metal singer trying to sound as intimidating as possible. Hell, it even has a Jabba the Hutt-style chortle.

Closer alignment with traditional archetypes of monsters does not necessarily make a monster more frightening or impactful. Nor does higher production values and detail in its presentation. Consider Forbidden Planet, which presented one of the scariest monsters in cinematic history via nothing but emphatic howling noises and a bunch of red scribbles.

Black Mesa is a highly impressive update of a highly innovative game, making full use of what an advanced engine has to offer while increasing much-needed gameplay and trimming what was unneeded in the original game. It can certainly be recommended to someone who wants to play the Half-Life games in chronological order or the order of their release, unless they’re a purist. But it needs to be considered that perhaps some of the content in the original Half-Life lacked further detail by intention, rather than due to the limits of its technology.